Microplastics in sinking particulate matter of the Inner Sea in the Maldives

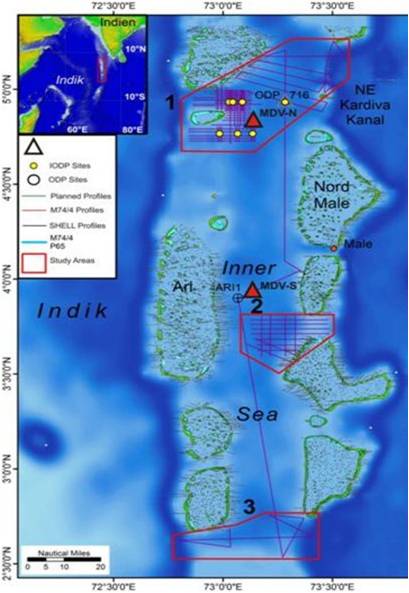

The Maldives, a tropical paradise, known for its overwhelming marine splendor with 1,190 small islands grouped in two chains of 26 atolls that surround the so-called “Inner Sea” (see Fig. 1). It is also a country, however, for which many of the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are extremely urgent. For example, with 80% of land lying less than a meter above average sea level, climate change and sea level rise are pressing concerns. Even by conservative estimates of sea-level rise due to global warming, 77% of its land could be lost to the sea by 2100.

Fig. 1: Location map of the Maldives and position of the sediment trap moorings deployed in 2014 in the northern (MDV-N) and southern (MDV-S) part of the Inner Sea (modified according to Betzler, 2015).

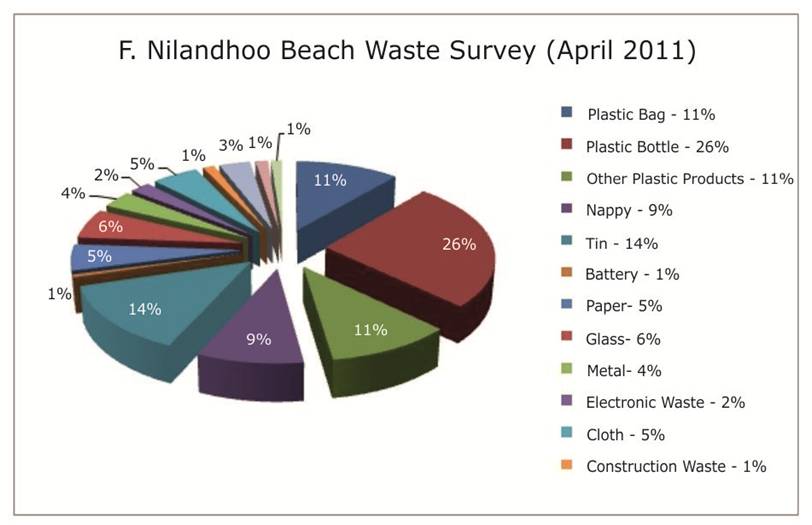

A more immediate concern is the issue of waste management. According to UNICEF (2019) 280,000 plastic bottles are used and discarded daily in the capital city of Malé alone. Statistical data released by the Maldives Customs Service document that 325 million plastic bags were imported into the Maldives between 2006–2010 (Zuhair, 2011); the import increased dramatically to 104 million plastic bags in 2018 (UNICEF 2019). Due to this extensive consumption and the mismanagement of waste, even uninhabited islands of the archipelago are littered with plastic. For example, a beach waste survey conducted in April 2011 in the island Faafu Nilandhoo revealed that 57% of waste (in total 9066 items) located along the shoreline and beach area were products of plastic: 26% were categorized as plastic bottles, 11% as plastic bags, 9% as diapers and 11% as other products of plastic (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Types of waste found alongshore Faafu Nilandhoo Island in April 2011 (modified after Zuhair, 2011).

Unlike organic waste, plastic can take hundreds to thousands of years to decompose in nature. Plastic waste is causing floods by clogging drains, causing respiratory issues when burned, shortening animal lifespans when consumed, and contaminating water bodies when dumped into canals and oceans. In oceans, plastic is accumulating in swirling gyres that are miles wide. Saltwater, solar radiation and mechanical abrasion through wave movement, causes plastic to be fragmented into microplastics, that are almost impossible to recover and that are disrupting food chains and degrading natural habitats. For the Maldives, which is heavily dependent on tourism and its marine resources, the problem of plastic pollution is therefore of growing concern.

Recently the Maldivian government has taken important steps to protect this tropical paradise such as by banning the use of single-use plastic bottles, prohibiting the importation of non-biodegradable plastic bags and of other wastes for which there is little or no opportunity to recover or recycle. Fishermen are asked to sweep plastic waste from the sea while they fish, shipping it back to the capital Malé, where it will be transferred to long-distance ships for recycling into plastic-based fabrics.

While large plastic objects on beaches and in the water are easy to spot, there is a growing need for knowledge about the microplastic contamination of the Inner Sea. In a first step, information is needed on the amount and type of particles present in the water column and on the processes that control their input, their floating behavior and/or their deposition.

In 2014, within the framework of the BMBF-funded project “Maldivian Monsoon and Carbonate Platform Processes”, headed by the Institute of Geology of the University of Hamburg, two mooring arrays were deployed in the northern and southern part of the Inner Sea (see Fig. 1). Sediment traps were attached to the mooring at 80 and 200 m water depths and programmed to collect sinking particulate matter at 18-day intervals for 1 year. The time-series covers the SW- and NE-monsoon seasons with strong fluctuations in precipitation, wind strength, aeolian input, surface and deep-water currents, primary productivity, and inflow of water from the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal.

As an accompanying study to this project, sub-samples of the trapped material will be analyzed qualitatively and quantitatively for plastic particles in the laboratories of the Microplastics Research Group of CEN. Preliminary results show that microplastics are ubiquitous in relevant concentrations. In addition to the development of a digestion method suitable for the samples from the Maldives, the work includes the type- and size-specific analysis of the particles using RAMAN spectroscopy.

Project participation: Felix Pfeiffer, Martin G. Wiesner, Niko Lahajnar, and Elke Kerstin Fischer